Is Excessive Endurance Training Putting You at Risk?

In April 2016, nearly 40,000 runners gathered at the starting line for the London Marathon. 31-year-old British Army captain David Seath was among them. An experienced athlete and combat veteran who was running to raise money for injured soldiers, he completed the first part of the course with no sign of distress. But three miles from the finish line, he suddenly collapsed. Despite immediate medical attention, Captain Seath was pronounced dead soon after arriving at the hospital. The cause of death: Sudden cardiac arrest from a previously undetected heart defect, one which may have been linked to his long, challenging runs.

Your reasons for exercising doubtless include its positive health effects. Regular physical activity promotes increased strength and flexibility, reduced stress, a tougher immune system and—as you’ve heard many times before—a healthier heart. But could your training actually be putting your heart at risk?

Mounting evidence suggests that endurance athletes, especially marathoners and triathletes, are susceptible to a group of related cardiac conditions. The stress of these demanding events can damage the heart, causing dangerous, potentially fatal complications.

Since the heart is a muscle, it naturally gets larger the more intensively it’s worked. Increased volume and pressure loads cause the heart’s lower left chamber, or ventricle, to enlarge and thicken; this common condition is called left ventricular hypertrophy, or “athlete’s heart.” Ironically, a larger heart doesn’t necessarily mean a stronger one. Bigger cardiac walls lead to reduced overall efficiency, causing the heart to have to work harder to keep pace with the body’s demands. Fortunately, athlete’s heart is a non-fatal, generally non-dangerous condition. Its primary threat is that it can mask the symptoms of other, more serious issues.

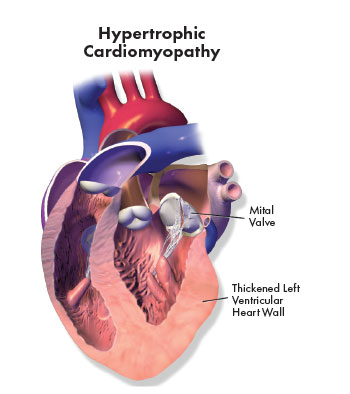

In a minority of cases, however, and especially among endurance athletes who train for more than an hour a day, more concerning heart problems can develop. These include irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia) and general thickening of the heart muscle (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or HCM). Either of these factors—or, as is commonly seen, the presence of both—may lead to sudden cardiac arrest.

Unlike a heart attack, in which the loss of blood supply causes the heart muscle to die, sudden cardiac arrest is caused by a problem with the electrical signals that direct a heart to beat strongly and steadily. Early symptoms may include shortness of breath, chest palpitations, or fainting; more commonly, though, there is no warning before the heart simply stops pumping blood.

Both the relatively benign athlete’s heart and its more dangerous cousins typically produce no symptoms. Your doctor can easily detect a resting heart rate of less than 60 beats per minute (bradycardia) during a routine checkup and may recommend further testing. However, distinguishing athlete’s heart from HCM requires more detective work.

A recent study by Australian and Belgian researchers suggests that in order to successfully diagnose exercise-related heart problems, doctors should take an active approach. “You do not test a racing car while it is in the garage. Similarly, you can’t assess an athlete’s heart until it is under the stress of exercise,” said study author Dr. Andre La Gerche in a journal news release. La Gerche and his fellow authors prescribe electrocardiogram testing on a treadmill for an accurate picture of the heart’s overall health.

Or, if an enlarged heart is confirmed but its cause is unclear, other authorities recommend stopping endurance activities for three to six months to see if heart wall thickness decreases. A heart that returns to normal size indicates athlete’s heart, while one that remains enlarged is an indication of HCM.

Of course, as with any medical condition, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. So how much endurance training is too much? Extensive research suggests that the health benefits of exercise top out at about 10 metabolic equivalents (METS), a level far below that attained during a sprint or a 25-mph bike ride.

But, as Dr. La Gerche writes, “All athletes know that their motivation… [is] not based on statistics but on the immediate satisfaction that comes from practice. You are more likely to be killed by a car when riding than you are to die of a heart attack, and yet cyclists do not spend all of their cycling hours avoiding this risk on a wind trainer.” With a clear bill of health from your doctor and a clear understanding of the risks, you should feel confident tackling that next marathon or hill climb—wholeheartedly.

Photo Credit the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy image: CC: Blausen.com staff. “Blausen gallery 2014”. Wikiversity Journal of Medicine. DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 20018762.